Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder globally, trailing behind Alzheimer's. Tremors are a hallmark of PD, but advancements in research have led to a renewed recognition of the condition's complexity. It is now widely appreciated that PD can manifest in diverse ways, and not all individuals with the illness experience the same set of motor symptoms. One may have hand tremors, and another may have difficulty walking. Yet another person may have overwhelming anxiety.

This has experts looking beyond tremors in PD and taking a spectrum of motor challenges—muscle stiffness, loss of balance, slowness of movement—into account for studying, diagnosing, and managing the condition. They believe that a focus on understanding how and why movement is widely impacted will help decode the enigma of PD and pave the way for innovative approaches that can tangibly track the disease's progression.

This article covers:

- What is Parkinson's disease (PD)?

- Why is movement affected in PD?

- What are the different types of motor symptoms of PD?

- How do researchers and clinicians use movement tracking for PD?

- How has the understanding of PD evolved with movement-tracking technologies?

- Are there differences in the effectiveness of these technologies between men and women?

What is Parkinson's disease—and why is movement affected?

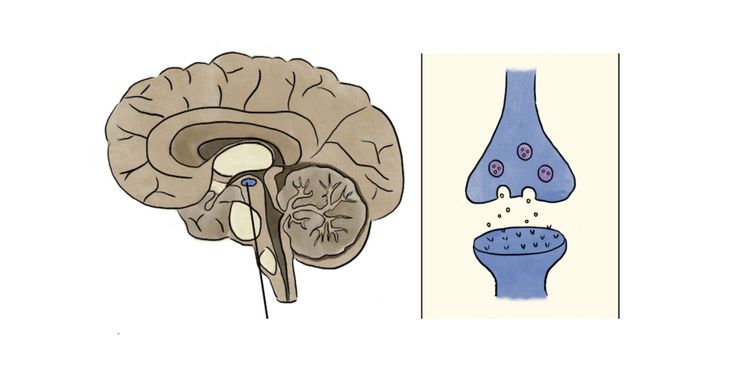

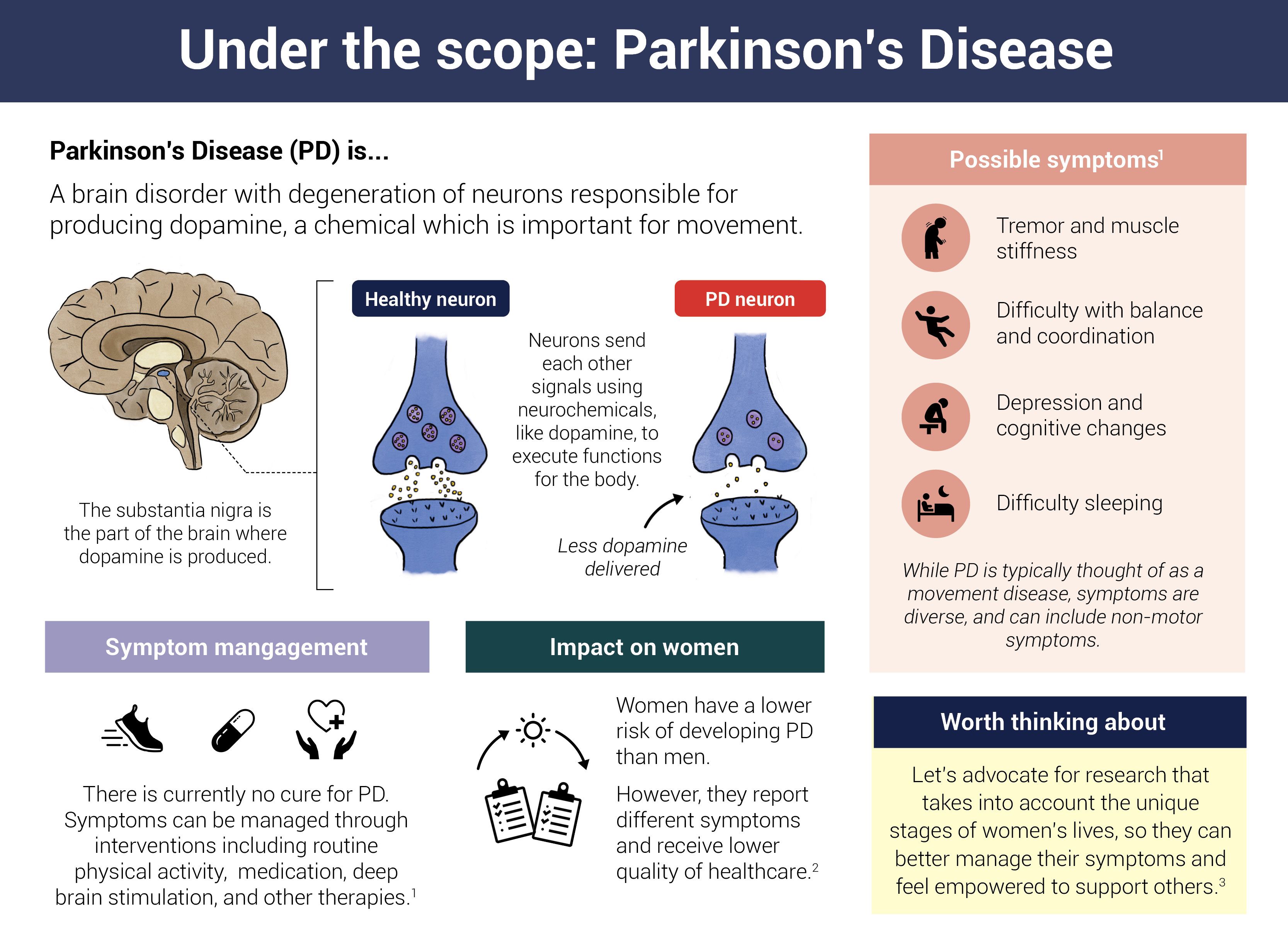

In most PD cases, the triggers of the condition remain elusive. (An amalgam of genetic and environmental factors is likely at play.) However, the disease consistently involves a decline in dopamine levels in specific brain circuits. Dopamine is a vital chemical messenger produced in a region in the brain known as substantia nigra, that transmits signals between neurons.

The basal ganglia, a group of structures near the brain's center, control the body's voluntary movements through a complex network of brain circuits. These circuits rely on chemicals like dopamine, produced in the substantia nigra, for exchanging information that helps initiate, execute, and inhibit movements.

In PD, clumps of sticky proteins, known as Lewy bodies, begin to accumulate within dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, clogging crucial cellular processes. Gradually, these neurons degenerate and die off, resulting in dwindling dopamine levels and faltering communication within the basal ganglia. As a result of this damage, people develop movement problems like tremors—often the first signs of the disease.

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below)

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below)What are the different types of motor symptoms of PD

Together, these changes in movement form a spectrum of observable symptoms directly linked to the changes in the brain due to Parkinson's disease.

1. Tremors and fine motor skills

Tremors, especially at rest, are an early indicator of PD. The nature and frequency of these tremors can evolve over the course of the disease, and tracking these changes helps experts gauge how quickly the condition is progressing. Changes in fine motor skills, such as handwriting becoming smaller (progressive micrographia), can also be subtle yet common hints of the condition.

2. Bradykinesia and slowness of movement

Bradykinesia, or slowness of movement, occurs when people with PD struggle to initiate and complete daily tasks. As the condition advances, these difficulties become more apparent and disruptive.

3. Rigidity and muscle stiffness

Muscle stiffness serves as a valuable indicator of the condition's severity. It arises from heightened muscle tone or tension in muscles even at rest. As PD progresses, muscle tone in the neck, shoulders, and limbs can intensify, making it more challenging to fulfill daily activities like walking, dressing, eating, and even maintaining posture.

4. Postural instability and balance challenges

Postural instability becomes pronounced in the later stages of PD, leading to difficulty maintaining balance and an upright posture.

5. Gait disturbances and walking patterns

People with PD experience gait disturbances like a shuffling walk, reduced arm swing, and difficulties initiating or stopping the walking motion. Additionally, the onset and frequency of episodes known as "freezing of gait (FoG)," where an individual feels stuck mid-step, indicate the disease's progression.

How do researchers and clinicians use movement tracking for PD?

Movement tracking in Parkinson's isn't new. Experts use clinical assessments and subjective observations to diagnose and treat the condition. For example, neurologists routinely use the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) to score patients on a standard set of movements and gauge the severity and progression of PD. They also observe patients during clinic visits and may have patients track and report their symptoms.

However, these traditional methods have their limitations. For some people with PD, symptoms like tremors are subtle and only show up during specific movements. For others, the disease progresses rapidly, with new symptoms emerging between clinical evaluations.

An alternative and emerging approach involves movement tracking using digital technologies like wearable devices with motion sensors. The thinking goes that continuous collection of objective data about how a person with Parkinson's moves can offer greater insight into the condition than the occasional pen-and-paper assessment.

Fine-grain measurements of movement with wearable sensors could also allow:

- earlier diagnosis of the disease, before movement changes are observable to the naked eye,

- differentiation of Parkinson's from other disorders with similar symptoms,

- measurement of patients’ responses to disease-modifying therapies.

How has the understanding of PD evolved with movement-tracking technologies?

Last year, a team of researchers at the University of Oxford tested two different movement-tracking approaches on the same set of patients—one using 12 sensors to measure everything from the direction of toe movement to stride length, and the other standard clinical assessments every three months.

They found that the sensors did a much better job at picking up subtle nuances in movement compared to the typical PD rating scale used in the clinic.

However, another study found that movement-tracking devices can reliably measure gait disturbances but not disease progression.

Based on this type of evidence, the U.S. FDA has approved applications like NeuroRPM that can do this tracking outside the clinic with nothing but an Apple Watch.

Are there differences in the effectiveness of these technologies between men and women?

But there's a long road ahead before this approach becomes widespread. For one, women are historically underrepresented in clinical trials, including those focused on PD and wearable technologies. Women also tend to experience different motor and non-motor symptoms than men, so for digital tracking to become the norm, wearables must be able to capture and assess gender-specific differences accurately.

As technology advances and more comprehensive studies are conducted, wearables may become more accurate and effective. Until then, they represent an opportunity but not a breakthrough in PD.

Infographic references

- Parkinson's Disease, National Institutes of Health (Accessed June 9, 2023)

- Women and PD, Parkinsons.org (Accessed June 9, 2023)

- Subramanian, I., et al. Unmet Needs of Women Living with Parkinson's Disease: Gaps and Controversies. Movement Disorders, Vol. 37, No. 3, 2022