Oct 18, 2023, 4:00 am UTC

6 min

Created by

The complicated reality of motherhood: Postpartum depression

This article covers:

- What is postpartum depression (PPD)?

- What are the other perinatal mental health conditions?

- How does PPD differ from the "baby blues" and other types of depression?

- What are the signs & symptoms of PPD?

- What causes PPD?

- Who's at risk of PPD?

- What is the impact of PPD?

- What should you do if you think you have PPD?

- What treatments are available for PPD?

Becoming a mother marks the start of a lifelong journey of love, selflessness, and dedication. But the transition to motherhood can also be intensely challenging.

An estimated 1 in 5 women experience crippling sadness during what is usually cast as one of "the happiest and most rewarding" times of their lives. And the saddest part? Postpartum depression (PPD) continues to be one of the worst-kept secrets about motherhood, with as many as half of new moms with PPD going undiagnosed.

Postpartum depression, also known as peripartum depression, is a serious but treatable medical illness involving feelings of extreme sadness, indifference and/or anxiety, as well as changes in energy, sleep, and appetite. It carries risks for the mother and child.

Fortunately, new hope for these women — and their families — is emerging. In the past decade or so, the stigma around PPD has begun to lift, scientists are developing new drugs that target its specific chemistry, and research is revealing the superpowers of the maternal brain.

Find out how PPD differs from other types of depression, the red flags you should look out for, and which new treatments are on the horizon.

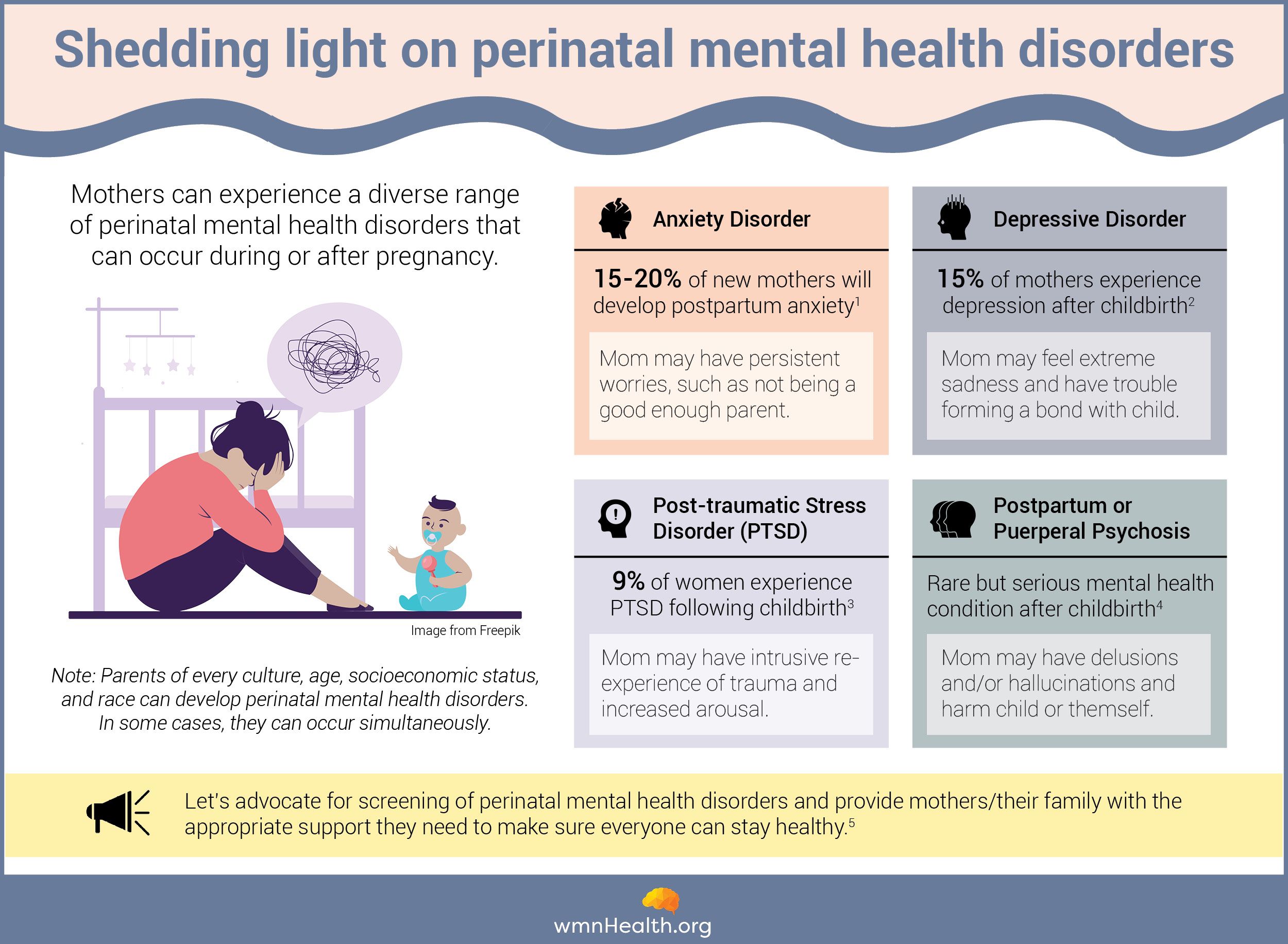

Among perinatal mental health conditions, postpartum depression generally receives the most attention. But there is growing recognition of a spectrum of conditions, including postpartum anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis. (References below)

Among perinatal mental health conditions, postpartum depression generally receives the most attention. But there is growing recognition of a spectrum of conditions, including postpartum anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis. (References below)How does PPD differ from the "baby blues" and other types of depression?

Most new parents experience the "baby blues" — mood swings, crying spells, anxiety, and difficulty with sleeping — that resolve a week or two after childbirth. But PPD is different. PPD symptoms are much more intense and last a lot longer than those associated with the baby blues.

Teasing out the differences between baby blues and PPD can be challenging because PPD can also begin within the first month of childbirth. In contrast with the baby blues, PPD symptoms are much more intense and last a lot longer.

PPD was added to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-4) in 1994. Before then, many mental health professionals argued that there were not enough unique features of PPD to warrant a separate disease category.

Today, the debate continues, and researchers are still working to understand how PPD manifests in the brain and untangle how it differs from other types of depression. What sets PPD apart, according to brain experts, is timing: While women can experience depression at any point during their lifetime, PPD symptoms usually show up within eight weeks after childbirth and last longer than two weeks.

What are the signs & symptoms of PPD?

PPD can be challenging to identify, as many symptoms overlap with the stress and fatigue associated with new motherhood. Some of the common signs and symptoms of postpartum depression are:

- Persistent feelings of sadness, restlessness, dread, or hopelessness

- Substantial changes in appetite

- Extreme fatigue (sometimes coupled with insomnia)

- Low self-worth

- Intense irritability

- Withdrawal from loved ones

- Brain fog that leads to trouble concentrating, remembering, or making decisions

- Loss of interest in pleasurable activities/ hobbies

- Persistent physical signs, such as headaches or an upset stomach

- Thoughts about self-harming or harming the baby

What causes PPD?

Multiple factors likely contribute to PPD, including hormonal fluctuations that occur during and after pregnancy, along with various psychological, social, genetic, and environmental factors.

In the weeks following childbirth, hormonal changes — specifically, a drastic drop in levels of estrogen and progesterone, which are elevated during pregnancy — can trigger symptoms of depression.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the first oral medication, Zuranolone, for treating PPD. It mimics allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid that protects the brain from stress during pregnancy. Allopregnanolone levels rapidly decrease after childbirth, and this change is believed to contribute to PPD. The drug then targets parts of the brain involved in mood and stress regulation to resolve symptoms of PPD rapidly.

Other factors — other than hormonal fluctuations — make women more susceptible to this type of depression and need to be considered when treating it.

However, there isn't sufficient data to conclude hormones are the only cause. Some scientists like Suzanne O'Brien at the National Female Hormone Clinic in London are looking at other factors — like a history of depression — to get to the heart of the mechanisms separating PPD from different types of depression.

In a recent study, O'Brien and her colleagues studied the amygdala response to emotional stimuli in mothers with a history of PPD during a part of the menstrual cycle that mimics hormonal changes after childbirth. The amygdala is a part of the brain involved in regulating emotions like fear, anxiety, and anger.

The researchers compared the results with the amygdala response of women with no history of depression and others with a history of depression outside childbirth. They found that in women with a history of PPD, the amygdala was less responsive to positive stimuli than the control groups.

This study, among others, reveals that while PPD and other types of depression affect similar parts of the brain, such as the amygdala, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus, the way PPD modifies functions of these regions is quite different from what is seen in other mental health conditions.

Who's at risk of PPD?

Other than hormonal fluctuations, there's an array of factors that make women more susceptible to this type of depression and should be considered when treating it. They include:

- Personal or family history of depression and other mental health conditions

- Inadequate social and emotional support, including poor partner satisfaction

- Financial stress

- Medical complications during childbirth

- A stressful life event during pregnancy or after childbirth, such as the death of a loved one, personal illness, or domestic violence and instability

- Unplanned or unwanted pregnancy

- First-time motherhood, very young motherhood, or older motherhood

What is the impact of PPD?

While experts are still putting together pieces of the puzzle, one thing's clear: PPD, when left untreated, threatens the mother, the baby, and the entire family unit.

PPD is also the strongest risk factor for maternal suicide, a leading cause of maternal mortality within the first year of childbirth.

23% of pregnancy-related deaths in the United States (2017-2019) were caused by mental health conditions.

Mothers with untreated PPD are also at higher risk for substance use, which, in the face of trauma and a lack of mental health resources, can become a coping mechanism, and they may struggle to bond with their babies. And studies have shown mothers with untreated PPD are more likely to experience depressive episodes later in their lifetime.

These impacts have a ripple effect on the family: Children of mothers with untreated PPD are likely to experience developmental and behavioral challenges, intergenerational trauma and mental health problems that persist throughout their lifetime.

What should you do if you think you have PPD?

If you think you or a loved one might have PPD, it's essential to seek advice from a doctor or a mental health professional. These experts will typically use a screening tool, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Screen (EPDS), that asks mothers to validate statements like, "I have been anxious or worried for no good reason," or "I have been so unhappy that I've been crying."

While studies have shown screening tools like EPDS don't always work, they can help doctors identify mothers who risk developing PPD earlier or help people who might not realize what their symptoms mean.

When access to a professional is limited, free self-screening tools developed by credible organizations, such as Mental Health America, can help you get some answers. However, these PPD screeners are not designed to diagnose the condition — only a mental health professional can do that.

If you need help immediately, call the National Maternal Mental Health Hotline at 1-833-TLC-MAMA (1-833-852-6262).

(US only)

What treatments are available for PPD?

If you are diagnosed with PPD, here's what your treatment options might look like:

Professional advice that empowers:

Speak with a licensed therapist equipped to listen to you and teach you skills that will help you cope with PPD. Postpartum Support International can help you find experts near you and essential information on the condition.

PPD medication that supports health and wellness goals:

Ask your doctor whether taking medication for PPD is the right option for you. Brexanolone and Zuranolone are the only two drugs available in the U.S. that are specifically designed to treat PPD. But, other types of anti-depressants are frequently prescribed by experts and have been shown to improve symptoms.

Self-care that nourishes the brain and body:

Do your best to get as much rest and sleep as you can. Try to eat nutritious food, including lots of greens. Once you have your doctor's approval, slowly engage in physical activity. Lastly, schedule pleasure into your everyday routine, such as taking a shower or catching up on a TV show you like.

Social support that heals:

Isolation can worsen PPD. Consider joining a support group for new parents so you are surrounded by others facing similar circumstances — this can elevate feelings of guilt and isolation. Postpartum Progress has compiled a comprehensive list of postpartum support groups across the U.S. and Canada that you can consult. If that's not the right option, try to talk about your feelings and needs openly with family and friends.

A word from wmnHealth

Guilt and shame are just some barriers that continue to hold women back from asking for help. You don't have to go it alone. You can change the conversation on motherhood around you by sharing your experiences and encouraging others to shine a light on their journey with PPD.

Infographic references:

1) https://www.npjournal.org/article/S1555-4155(20)30452-9/fulltext

2) https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/depression/

3) https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/postpartum-post-traumatic-stress-disorder/

4) https://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/postpartum-psychosis/

5) https://www.cmaj.ca/content/194/43/E1487