Imagine walking down a busy street — screeching brakes, wailing sirens, cars whizzing by. There's no escaping the chaos of living in a city.

No wonder research suggests people living in dense urban areas are unhappier and unhealthier. Their risk of developing depression, anxiety, and other mood disorders is much higher than those living outside the city. Chronic conditions like high blood pressure are also common.

The opposite is also true. The incidence rates of these health issues drop when people have better access to green spaces. Why?

"From the buildings we create to the parks we design, anything that alters the natural world has features that interact with the brain to produce positive or negative effects on our well-being," explains Kevin Bennett, a psychologist at the Pennsylvania State University, who studies the intersection of urban design and mental health.

So if the human brain and the environment are so deeply interconnected, what aspects of the urban experience are to blame for worsening mental and cognitive health among city dwellers? And can we leverage this relationship to bolster well-being instead?

Exposure to loud sounds triggers the brain’s “fight or flight” response, cuing the body to be on the lookout for danger.

Nature sounds can lower the body’s sympathetic response, which kicks in in stressful situations, allowing the body to relax.

Inside the urban brain

Cities change how people think and act, which are the basis of cognition and mental health.

The research underscores this link. It suggests that the human brain has yet to evolve to deal with the smells, sounds, sights, and feel of urban places. Exposure to loud sounds, for example, triggers the brain's "fight or flight" response when the amygdala, the emotional processing center of the brain, sends distress signals, cueing the body to be on the lookout for danger.

And noise isn't the only stimulus the urban brain is continually exposed to in cities. From big crowds to narrow streets lined with looming skyscrapers to blinding lights, the stressors in an urban environment are a world apart from those humans encountered as hunter-gatherer lifestyle humans, a lifestyle humans led for 90 percent of their existence as a species.

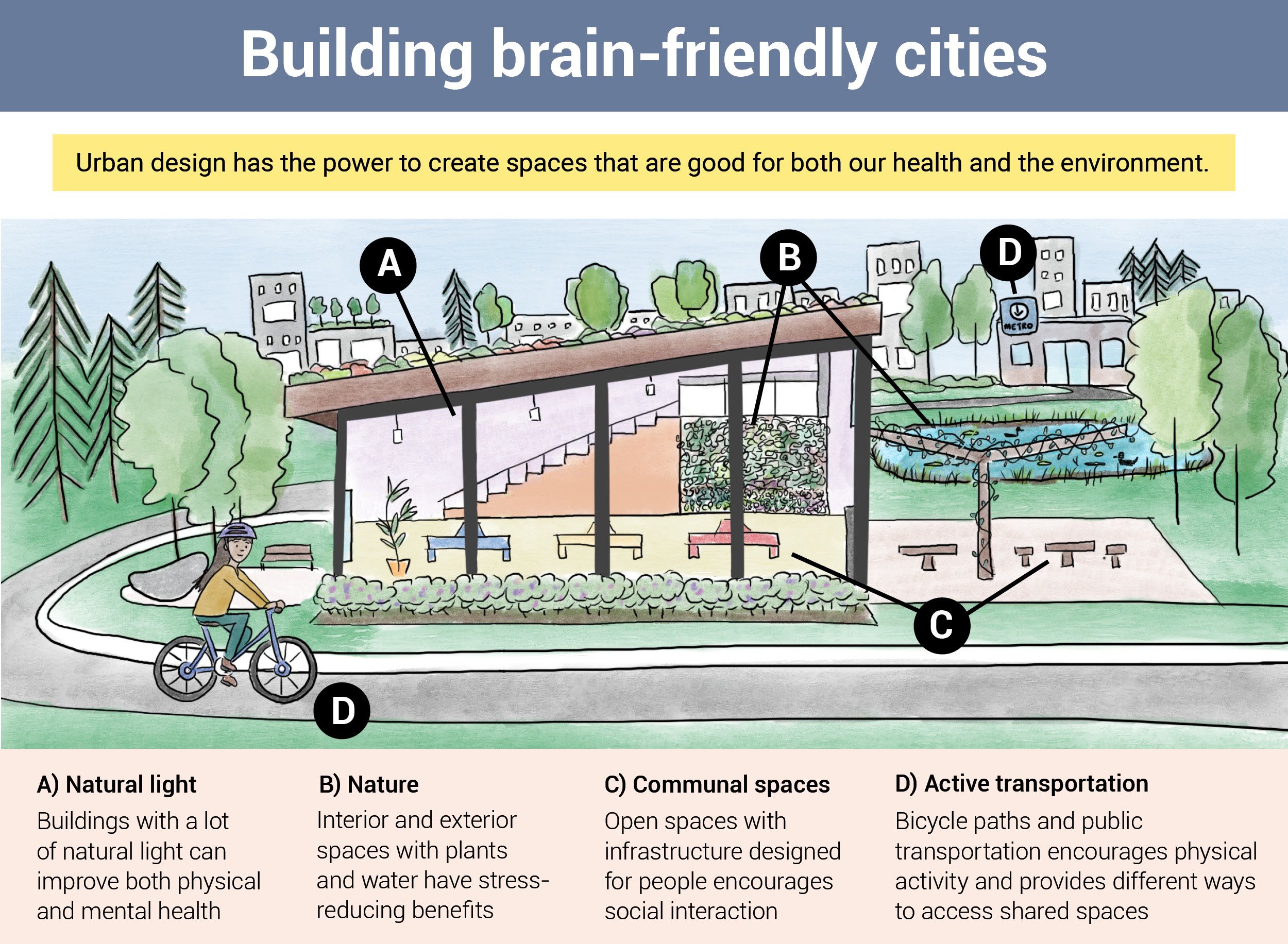

A growing awareness of the brain-and-environment connection among architects, neuroscientists, psychologists, landscape designers, and city planners is driving the development of wellness-driven urban spaces. This new approach to architecture and urban design integrates buildings with the surrounding environment and prioritizes city dwellers' physical and mental health. Brain-friendly design ensures that everyone has access to natural light, green, active, and social spaces — all of which offer an opportunity to connect with the natural world and a return to inborn and universal behaviors.

"I'm not saying we have to go back to the Stone Age and undo all the wonderful progress we've made with design and architecture," says Bennett. "But, [we should strive] to combine the modern features of architecture with the ancestral environment that's so important to us."

Exposure to natural light, for example, regulates the release of the hormone cortisol, which keeps us awake and alert during the day. And being near green and blue spaces makes us happier because we tend to prefer areas that once provided our ancestors with food, water, and safety.

Other aspects of the natural environment are important, too. Gazing at the horizon, for example, turns off an evolutionary stress mechanism in the brain that naturally narrows our field of vision, enhancing the brain's ability to focus on an immediate threat. In a busy city, our brain is constantly on the lookout for cars, bikes, traffic lights, and pedestrians, so being able to look at the horizon, for example, from a balcony or window, can widen our peripheral vision, producing a calming effect.

Building happier, healthier cities

While some cities like Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Calgary are redesigning public spaces to prioritize brain health, others are using research as a blueprint to build wellness-focused areas from the ground up. These spaces are meant to offer the urban brain what it craves — natural light, green and blue spaces, and areas to socialize.

Here are some examples of how people-centered design around the globe is changing the urban experience and offering a unique sense of safety, belonging, and connection to city residents:

- The Hogeweyk Dementia Village on the outskirts of Amsterdam is built for people with advanced forms of dementia. Its ample green spaces and winding streets lower stress levels, promote physical activity, and increase social interaction among residents.

- Superblocks in Barcelona are bigger than a typical city block but smaller than a neighborhood. The city is reclaiming part of the space occupied by cars and creating pockets of green space and public squares where citizens can connect with nature and participate in outdoor activities together.

- Youth mental health park in Calgary will feature spaces for group wellness activities, such as gardening and meditation, and areas for sensory relaxation, like swinging benches and a sensory garden.

Superblocks, like the one outside Barcelona's famed La Sagrada Familia, offer wide pavements, more plants and more spaces for meeting up and playing in.

The Superblocks Model

- Priority use for citizens

- Flat street design from façade to façade, with no asphalt road surfaces

- More greenery: From 1 percent to 10 percent

- Accessible streets

- New lighting system for a new atmosphere

- New furniture to encourage social use

- Promoting local commerce

The health benefits of green space aren't shared equally

Despite these efforts, for many city dwellers, particularly people of color, accessing pockets of restorative space remains a barrier. In fact, 76 percent of low-income, non-white individuals live in "nature-deprived" areas, according to a 2020 analysis by Conservation Science Partners.

How to connect with nature for your brain health

The U.K.'s Mental Health Foundation offers tips for building a connection with nature for those struggling to incorporate — or access — it in their everyday lives:

- Bring nature into your home by taking up gardening or getting a birdfeeder.

- Look after nature by joining a community conservation group.

- Find nature wherever you are by exercising outdoors and ditching the headphones.

- Exercise in nature by walking or running outdoors instead of in a gym.

- Connect with nature using all of your senses by listening for birdsong, looking for bees and butterflies, or noticing the movement of the clouds.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Get a weekly roundup of articles, inspiration, and brain health science in your inbox. Subscribe now.