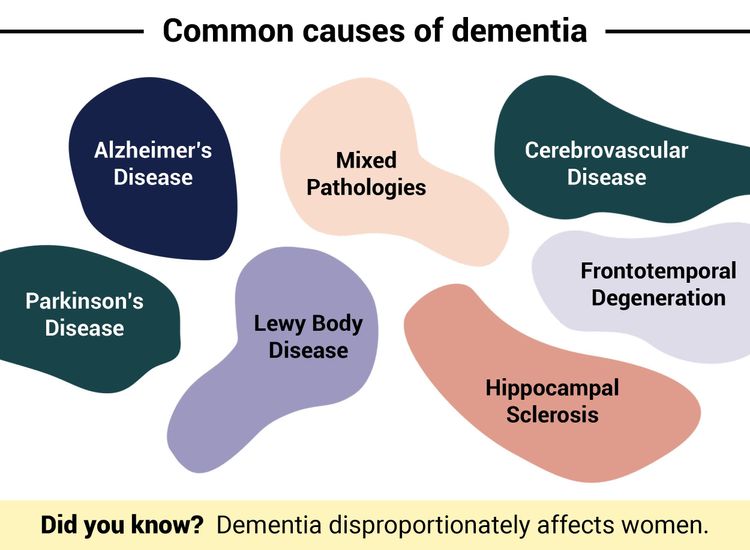

Dementia, a brain condition that affects memory, cognition, and social skills, hits women the hardest. In the United States, for example, more than two-thirds of those living with dementia are women.

In fact, it is so prevalent that women over 60 have a much higher risk of developing dementia than breast cancer — a leading cause of death among women worldwide.

For decades, experts have said the gender gap in dementia mostly comes down to one major risk factor: age. Women tend to live longer than men, so their lifetime risk of developing dementia is higher.

But increasingly, research hints that age is only half the story. An invisible, more insidious risk factor also drives disproportionately high dementia rates among women.

Signs and symptoms of dementia

Changes in memory that affect day-to-day activities

Difficulty performing familiar tasks

Reduced concentration

Changes in mood and behaviour

Experiencing confusion

Struggling to retain or process new information

Problems with movement and balance

Difficulty expressing emotions or putting thoughts into words

The puzzle of gender and dementia

Women's dementia risk is dramatically different than men's, and for years, experts have been looking for biological clues to understand why. Age is one of the strongest risk factors. However, studies show the prevalence of dementia is much higher in women even when compared to men of the same age, suggesting other factors are at play.

Some experts theorize the female-specific sex hormone, estrogen, may contribute to dementia risk. Levels of this "neuroprotective" hormone, which acts as a shield against damage and degeneration of nerve cells, decline following menopause, escalating women's risk of developing dementia.

But that still isn't the complete picture, according to Jessica Gong, a research fellow at University College London (UCL), whose research has focused on disentangling gender and sex differences associated with dementia.

How is dementia diagnosed?

Cognitive or neurological tests that assess memory and problem-solving skills

Brain scans that identify underlying causes of dementia, such as strokes and tumors

Psychiatric evaluation of mood and behavior, as well as other psychological conditions that accompany dementia

Blood or cerebrospinal fluid tests that measure levels of proteins associated with dementia

In a recently published analysis of 21 international studies on dementia, which included participants from 18 countries, Gong and her colleagues at the George Institute for Global Health in Australia looked at different risk factors, such as education, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and depression. Using data from these studies, they evaluated how each one influenced the likelihood of developing dementia in men and women.

The findings revealed a stark picture of inequalities.

"We actually found that diabetes and higher blood pressure pose a much greater risk of dementia in women than men," says Gong. "While we do need to delve a bit deeper into the biological mechanisms, it may be because women are less likely to get optimized treatment for these conditions, leading to the greater risk of developing other diseases, including dementia."

Gong and her colleagues also found that across high-, middle-, and low-income countries, women in low- and middle-income countries had the highest risk of developing dementia. This echoes patterns of gender disparities globally, in which women have unequal access to education, face gender-based violence, and have fewer career opportunities.

These social inequalities ultimately lead to lower cognitive reserve in women, according to Gong. This "reserve" builds up throughout a person's lifetime as they engage in stimulating activities. It acts as a safeguard against gradual damage to the brain and loss of cognitive functions in conditions like dementia.

"If a woman isn't able to gain that education at a younger age, or not really engage with the workforce in a stimulating way, her cognitive reserve will be much lower than of men who are doing those things, increasing her risk of developing dementia," says Gong.

Putting the pieces together

While the link between gender inequality and dementia rates has bleak implications for women's brain health, according to Gong, there are ways for women to build up a buffer that will help stave off conditions that lead to cognitive decline. This is how you can train your brain:

- Engaging in stimulating activities, such as solving a crossword puzzle or learning a new language

- Cultivating relationships in your community and prioritizing social interactions

- Managing other brain conditions, like stress and depression, that increase dementia risk

- Staying physically active

- Investing time in hobbies and activities that make you happier

Women can continue to live meaningful lives even after getting a dementia diagnosis. If you notice signs of the condition, it's important to seek help immediately to manage your symptoms and get the support you need.