Jan 19, 2024, 5:05 am UTC

7 min

Created by

What are disease-modifying therapies—and how are they revolutionizing MS care?

For most people diagnosed with a neurodegenerative disease, the future is bleak. There is no cure for these progressive conditions in which nerve cells slowly die, eventually robbing people of their capacity to move, remember, and even breathe.

However, the outlook for one condition — multiple sclerosis (MS) — is no longer so grim.

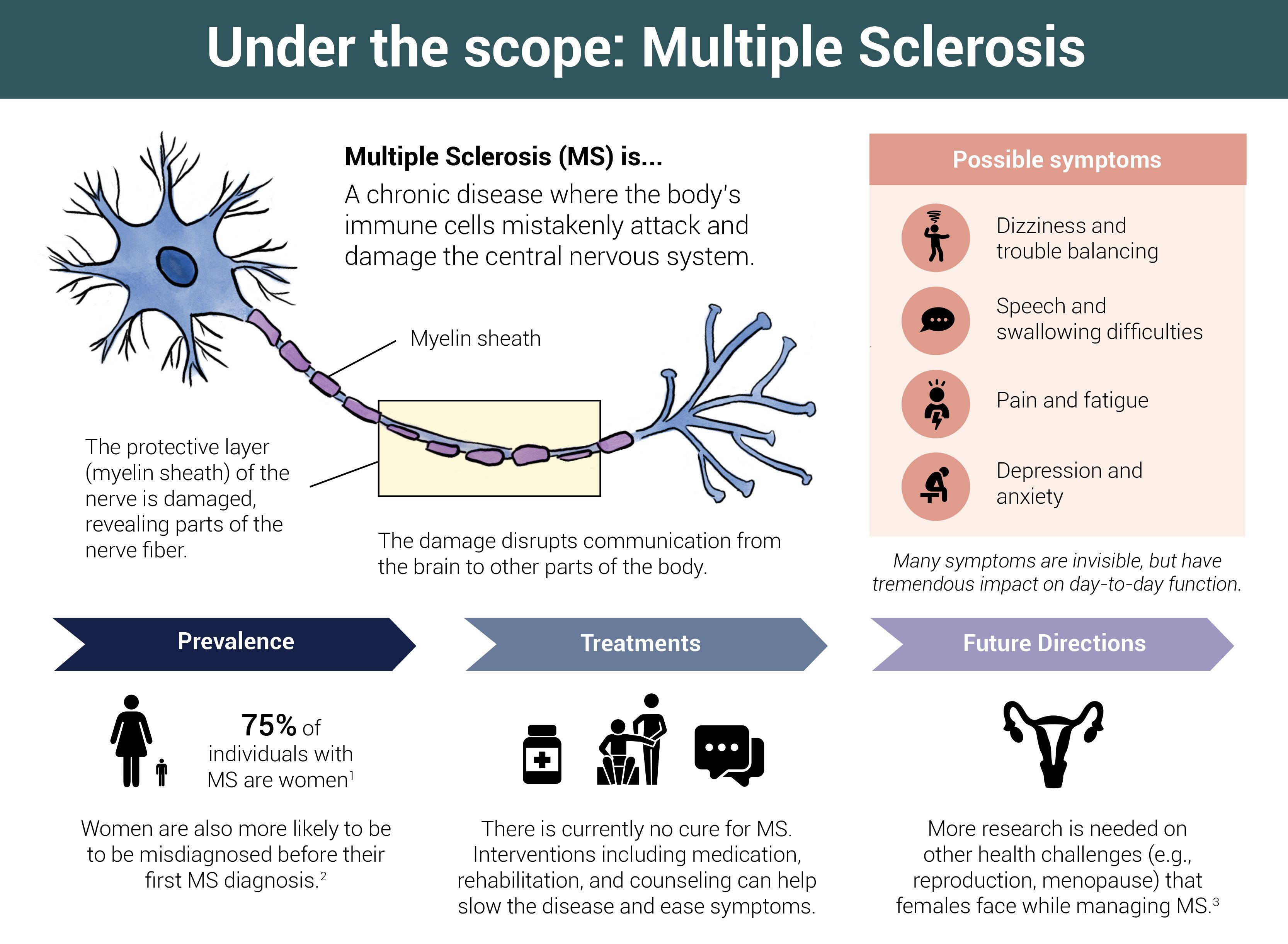

Over the past 30 years, there has been a quiet revolution in MS, a disease in which the immune system attacks and destroys myelin. This fatty sheath surrounds nerve cells and helps conduct signals from one cell to the next. When it is damaged, signaling falters and MS symptoms, often starting with fatigue, numbness, and loss of coordination, emerge.

Today, "disease-modifying therapies (DMTs)" fundamentally alter how the disease develops over time by interfering with abnormal changes in the body that are part of the disease process.

DMTs are considered the "holy grail" of neurology. While that metaphor is a little tired, the idea it captures is powerful: The development of DMTs for other neurodegenerative diseases—and the ability to alter or halt disease progression—would revolutionize treatment and transform the outlook for people living with these conditions and their families.

MS is proof positive. For many people with the condition—though not all—a diagnosis no longer means an inevitable and debilitating decline in their physical and mental abilities, a loss of independence, and a poor quality of life. Instead, MS has become a highly manageable condition.

"Today, a person whose MS is just beginning has an outstanding chance for a life free of disability. Whereas in the 1970s, the average person whose MS was beginning would be wheelchair dependent or worse within 15 or 16 years," says MS expert Dr. Stephen Hauser, Robert A. Fishman Distinguished Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF).

"I think this is one of the great success stories of modern molecular medicine," he says.

This article covers:

- What are disease-modifying therapies (DMTs)?

- Are disease-modifying therapies a cure?

- How do disease-modifying therapies work in MS?

- How have MS treatments evolved over the past 30 years?

- Can MS therapies reduce the progression of the disease?

- Are there differences in the effectiveness of MS therapies between men and women?

What are disease-modifying therapies (DMTs)—and how do they differ from symptomatic therapies?

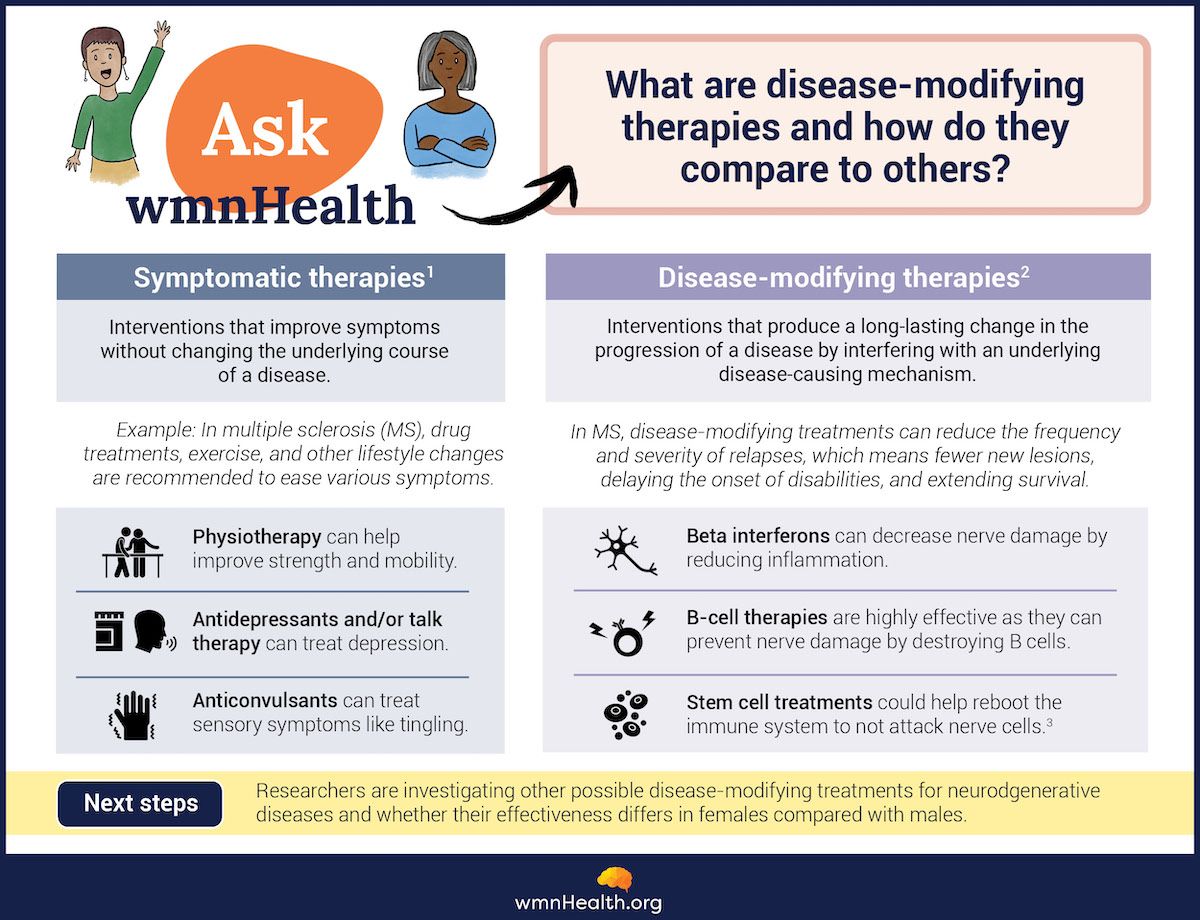

Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) change how a health condition progresses by modifying the underlying disease processes. For example, statins, one of the most widely prescribed drugs in the world, are considered a disease-modifying therapy for heart disease because they reduce a person's risk of heart attack and stroke by lowering cholesterol levels in the blood. They are different from symptomatic therapies, which address the symptoms of a disease but do not alter its course. Other common DMTs are chemotherapy drugs for cancer and anti-rheumatic medications for arthritis. These treatments get at the root of a disease, not just how it manifests.

Disease-modifying therapies get at the root of a disease, not just how it manifests.

DMTs are usually drugs — but not always. Cell-based therapies (e.g., CAR-T and stem cells) and lifestyle modifications (e.g., exercise) can also change how a disease develops. CAR-T cells are often used to treat blood cancers like leukemia. They are immune cells engineered to recognize, attack, and kill a person's cancer cells. Similarly, stem cells can be engineered to repair or regenerate damaged tissue. Though the vast majority of stem cell therapies are experimental, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved two stem cell therapies for sickle cell disease, a life-threatening genetic disorder. Blood stem cells are harvested from a person with sickle cell disease, genetically modified to produce oxygen-carrying proteins, and then infused back into their bloodstream. This prevents clots and blockages from forming in blood vessels and the tissue damage that ensues.

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)How do disease-modifying therapies work in MS?

Most MS therapies target the immune system and change how it behaves. The aim is to reduce inflammation caused by the misdirected immune attack, reducing damage to the nervous system. Some DMTs trap immune cells in specific parts of the body where they can do less harm, others interfere with signaling molecules that promote inflammation, and others block or kill particular types of inflammatory cells in the bloodstream.

The results can be profound. DMTs can dramatically reduce the frequency and severity of MS relapses, also known as flare-ups, when a person's symptoms temporarily worsen. This is important because relapses affect approximately 85 percent of people with MS and occur an average of once every two years. By limiting relapses, DMTs decrease and delay the nerve damage that relapses cause, helping to stave off long-term disability.

MS therapies are much less effective at treating progressive MS, a slow accumulation of disability without defined relapses.

(Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)

(Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)How have MS treatments evolved over the past 30 years?

In 1993, MS became a treatable disorder. The FDA approved the first MS treatment—a drug called interferon beta-1b—based on evidence that it could reduce the number and severity of relapses people experienced.

Beta interferons are proteins that regulate the immune system. They reduce inflammation by tamping down the activity of the immune cells that attack the nervous system in MS.

In addition to interferon beta-1b, scientists have developed other interferon beta therapies, and the drugs have become a mainstay of MS treatment. Long-term studies have shown that they can delay the development of disability and even improve survival rates.

In the 2000s, Hauser and other researchers began testing a different approach to MS treatment: removing B cells (B lymphocytes), a type of white blood cell, from the bloodstream. B cells protect the body from infection and other harmful substances by producing antibodies, Y-shaped proteins that bind to bacteria, viruses, and toxins and neutralize them.

Doctors and scientists have known for decades that antibodies, produced by incorrectly activated B cells, damage the nervous system in people with MS. Still, the scientific consensus was that T cells, another type of white blood cell, were the bad actors in MS.

"We were taught that those antibodies, made by B cells, were diagnostically essential but pathophysiologically completely irrelevant," says Hauser, who recounts his quest to find an MS treatment in a new book, The Face Laughs While the Brain Cries. "As it turned out, overturning in part that concept was to be the next 50 years of my professional life."

Indeed, B-cell depletion has transformed MS therapy.

Hauser describes the results of the first small trial of a B-cell depletion therapy: "When we first unblinded the first B-cell therapy in 2006—it was at 3 pm on a Friday afternoon, the last Friday in August. What we saw was amazing... We saw not only a giant effect on brain inflammation—an effect size that had not been seen before in almost any clinical trial—but the effect was almost immediate."

Types of MS

Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS): This type of MS is characterized by clearly defined attacks (relapses) followed by complete or partial recovery (remissions).

Secondary progressive MS (SPMS): Over time, most people with RRMS will transition to a phase of the disease called secondary progressive MS (SPMS). This phase of the disease has fewer relapses with variable disability progression.

Primary Progressive MS (PPM): Individuals diagnosed with this type of MS will experience a continuous worsening of symptoms from the beginning, usually without clear relapses or remissions.

Source: MS Canada

Since then, additional research has solidified the importance of B cells in MS, and several additional B-cell depletion therapies have been developed. They are used to treat both relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) — the most common type of MS—as well as primary progressive MS (PPMS), a rare type of the disease in which symptoms continuously worsen over time.

In an indication of how far MS treatment has advanced, the World Health Organization recently added 3 MS drugs to its Essential Medicines List. The move is intended to improve worldwide access to life-changing medications and establish a baseline of care for people with MS globally.

Can MS therapies reduce the progression of the disease?

The vast majority of MS drugs delay or prevent relapses. Progression—and with the continuous degeneration of nerve cells—remains challenging to treat.

"Our best current therapies are about 40 percent effective in early progression and about 30 percent effective in later progression. So, a big goal of current and future MS work is to make a greater impact against progression. That's truly the elephant in the room," says Hauser.

"For most people with MS today, a cure would mean stopping progression. And we're not there. But there are very hopeful ideas in the laboratory and the clinic."

Are there differences in the effectiveness of MS therapies in men and women?

The risk of MS in females far exceeds the risk in males, with about three times as many females as males being affected by the disease. There are also well-established sex differences in how the disease unfolds. For example, males are more likely to develop the progressive form of MS; they also tend to experience a more rapid progression than females. In contrast, females have a higher relapse rate and are more likely to experience poor outcomes compared with males.

What is less clear is whether MS therapies are equally safe and effective for men and women. A systematic review of 29 clinical trials on MS drugs found a "remarkable" lack of data on sex and gender differences, according to the authors.

Why? Because most trials don't evaluate sex, gender, and hormonal factors, they write.

In an interview about the research, co-author Dr. Riley Bove, a neurologist at the University of California, San Francisco, said, "We think there may be [gender differences in how men and women respond to treatment]. Men and women, in general, absorb and metabolize medications differently. Their immune systems are also slightly different, and so they may respond to certain immune modulators differently."

"That said, if we actually look at the data from the interventional clinical trials, we really just don't know enough right now," she said.

Researchers like Bove are calling for disease-modifying therapies to be tested on diverse populations and for clinical trials to assess whether people respond to treatment differently based on sex and gender.

"Hopefully, the newer studies will shine a more focused light on this question," according to Bove.

"We think there may be [gender differences in how men and women respond to treatment]. ... That said, if we actually look at the data from the interventional clinical trials, we really just don't know enough right now." — MS expert Dr. Riley Bove.

Are there emerging therapies in the pipeline for other neurodegenerative diseases?

In the past two years, the FDA has approved two DMTs for Alzheimer's disease. These new drugs are the first to slow cognitive decline in people in the early stages of the disease by reducing the buildup of toxic proteins in the brain.

They represent the tip of the iceberg: dozens of new drug candidates are being tested as DMTs—not only for Alzheimer's but also other types of dementia, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), raising the possibility that other neurodegenerative diseases may one day be as treatable as MS.

Not only that, Hauser says basic research on neurodegenerative diseases is pinpointing disease mechanisms that may be shared across different disorders. This increases the odds that what scientists learn about one disease can be applied to another. That may even hold true for emerging therapies.

"I think it's amazing how, today, the synergies of research across neurodegenerative conditions have come into focus," says Hauser.

"I think this confluence… in all sorts of neurodegenerative diseases is going to give us opportunities to bust down these silos and really understand how therapeutics might have value not only for the disease against which it's been developed but for others as well."

Infographic References

What are disease-modifying therapies?

- About MS. MS Society. https://www.mssociety.org.uk/

about-ms/treatments-and- therapies (Accessed January 17, 2024) - Disease modifying therapies MS Society. https://www.mssociety.org.uk/

about-ms/treatments-and- therapies/disease-modifying- therapies (Accessed January 17, 2024) - Stem cells. MS Canada. https://mscanada.ca/stem-cells (Accessed January 17, 2024)

What is multiple sclerosis (MS)?

- About MS. MS Canada. https://mscanada.ca/about-ms (Accessed January 17, 2024)

- The Gender Divide: Differences Between Men and Women With MS. MultipleSclerosis.net. https://multiplesclerosis.net/infographic/differences-men-women (Accessed January 17, 2024)

- Ross L, Ng HS, O'Mahony J, Amato MP, Cohen JA, Harnegie MP, Hellwig K, Tintore M, Vukusic S, Marrie RA. Women's Health in Multiple Sclerosis: A Scoping Review. Front Neurol. 2022 Jan 31;12:812147.