Jan 26, 2024, 5:00 am UTC

5 min

Created by

Q&A: Dr. Stephen Hauser on medical breakthroughs in multiple sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis (MS) has been Stephen Hauser's life's work. Since the 1970s, he has cared for people with MS and studied its underlying biology, driven by the desire to help patients navigate the crippling condition.

In his recent memoir, The Face Laughs While the Brain Cries, Hauser recounts his journey as a clinician-scientists and the eventual research breakthroughs that have changed the face of MS.

In this conversation, he talks about the development of B cell therapies for MS, where MS research is going, and what the convergence of research on neuro-immune mechanisms could mean for MS and other brain-damaging diseases.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

wmnHealth: What did MS treatment look like when you started your career — and what did that mean for patients?

Stephen Hauser: This is my 50th anniversary in MS research, and it is amazing to me how the landscape has changed. When I came into the field, there was nothing we could do for people with MS. There was also a therapeutic nihilism, a feeling that this was just so complicated that it made no sense to even try to find a treatment for patients. So, it was a very different world.

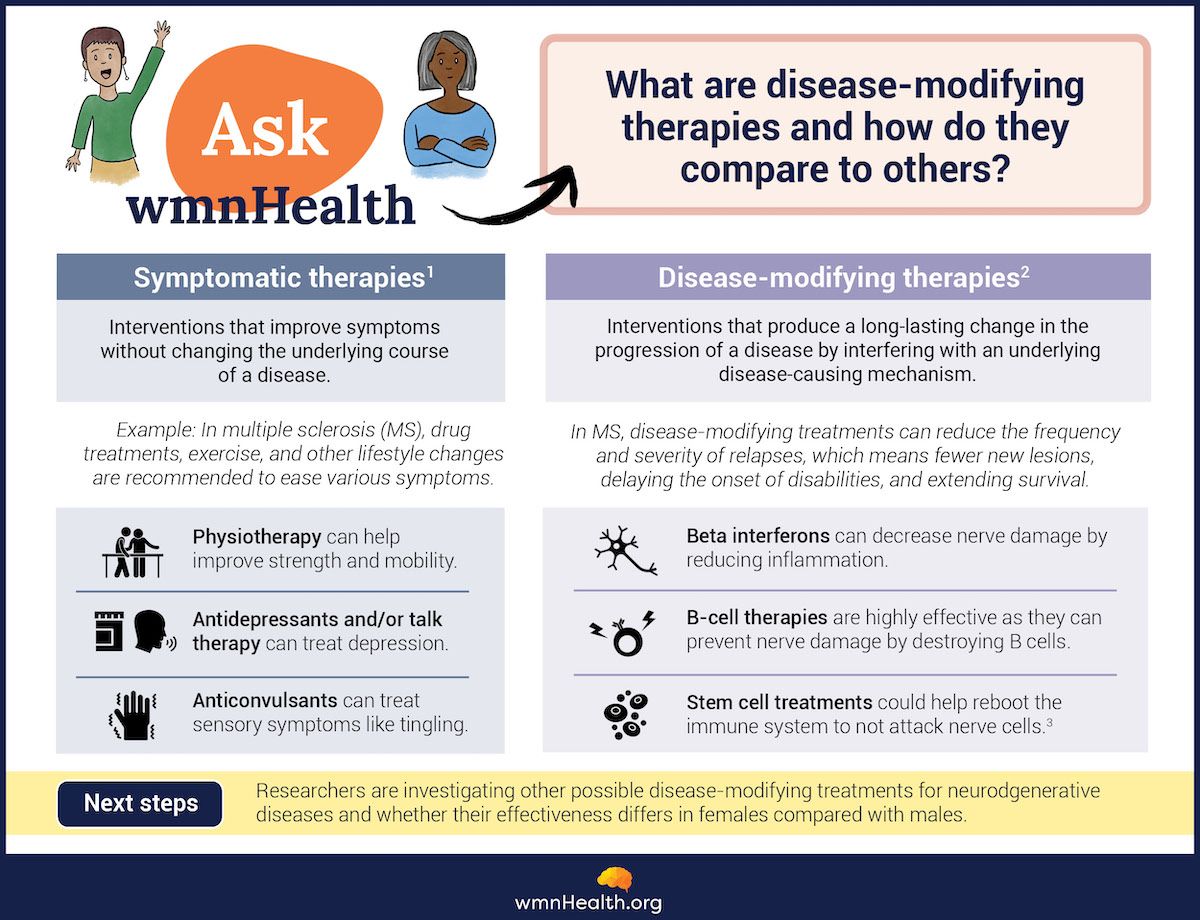

Fifty years later, there are more than a dozen "disease-modifying therapies" for MS. These medications can profoundly change how the condition develops. What have these treatments meant for people with the disease?

Hauser: Today, a person whose MS is just beginning has an outstanding chance for a life free of disability. Whereas in the 1970s, the average person whose MS was beginning would be wheelchair dependent or worse within 15 or 16 years [of diagnosis]. If you're 16 or 20 years old, that's when you're only in your 30s.

I think this is one of the great success stories of modern molecular medicine, and getting the word out about it was the main reason I wanted to write my book. I wrote it during COVID-19 when the public's confidence in science was being shaken. I also hoped the story would inspire some young people to pursue careers in medicine and science because of [the story's] inherent optimism and the remarkable idea that we could understand how nature works and use that to help people.

Infographic by Cat Lau. References below.

Infographic by Cat Lau. References below.The central story in your book is the development of B-cell therapies for MS. (B cells, or B lymphocytes, are a type of white blood cell made by the immune system to protect against infection.) How did the scientific orthodoxy about MS change because of this research?

Hauser: When I came into the MS field, it was known that we saw huge increases in specific antibodies in spinal fluid. These antibodies are known as oligoclonal bands. We used them in diagnosis, but we were taught that those antibodies, which are made by B cells, are diagnostically essential but pathophysiologically wholly irrelevant. The world believed that T cells [another type of white blood cell] were the cause of MS because they cause brain inflammation in mice. And as it turned out, overturning, in part, that concept was to be the next 50 years of my professional life.

When we unblinded the first B-cell therapy in 2006 — it was at 3pm on a Friday afternoon, the last Friday in August— what we saw was amazing. We expected to see just a tiny little bit of change because it was a small study with a single endpoint. We were hoping to eliminate the antibodies B cells were making. But we knew it would take a very long time for those antibodies to turn off. Instead, we saw not only a giant effect on brain inflammation—an effect size that had not been seen before in almost any clinical trial—but the effect was almost immediate. That told us that the 20 years of research on MS in animals had us directionally correct. But in terms of specifics, we were wrong. It couldn't have been the antibodies. It was the B cells themselves that were the culprits in the disease.

Let's dig into the role of B cells a little more. What is the understanding of their role in the disease today?

Hauser: The MS advance involved recognizing that B cells were at the center of orchestrating the damage [to the nervous system]. Multiple cells probably mediate the damage, but the B cells are the generals. We think B cells are probably doing two things. One, B cells are also talking very specifically to T cells, so we think that B cells are turning on a small population of culprit T cells responsible for inflammation, progression, and neurodegeneration. The second is that the genetic architecture of people predisposed to MS is dominated by pro-inflammatory B cells, which means that they're making more inflammatory and less anti-inflammatory chemicals. Those pro-inflammatory chemicals are turning on other cells nonspecifically and are a second cause of inflammation, cell damage, and progression. So, B cells are turning on T cells very selectively and turning on microglia, another type of immune cell that's gobbling up damage and healthy tissue, non-selectively.

Those are the two challenges for treating progressive MS. Can we turn off those two axes of communication: B cells with T cells, and B cells with microglia in the brain?

You mentioned microglia, another type of immune cell that appears to play an important role in Alzheimer's and some other brain diseases. Are there lessons from MS that apply to other neurodegenerative diseases?

Hauser: I think it's amazing how the synergies of research across neurodegenerative conditions have come into focus. In fact, through the American Brain Foundation, we're about to launch a $10-million blue-sky initiative for the best possible proposal to better understand immune abnormalities in brain-damaging diseases. I think this confluence, this coming together of neuro-immune mechanisms underlying tissue damage in all sorts of neurodegenerative diseases, is going to give us opportunities to bust down these silos and really understand how therapeutics might have value not only for the disease against which it's been developed but for others as well. This will be bidirectional, but I think it's more likely that advances in dementia will give us answers that will be useful to test in multiple sclerosis.

Given the success in MS treatment, I assumed it would be the reverse. That we might learn from MS how to treat other neurodegenerative diseases.

Hauser: I think there's been a dollop of good luck in our experience with MS. I also think that MS is more straightforward because so much of the disease takes place outside of the nervous system. In fact, the parts of MS that are within the nervous system, the progressive component, remain the challenge. Even if we have identified the right mechanism of tissue damage and can make an antibody to block it, we can't get therapeutic antibodies into the brain in sufficient concentrations to have the desired effect.

What's on the horizon for MS therapy?

Hauser: I think we're at a point in 2024 where we are beginning to think beyond disease suppression to a cure. But we have different ideas about what "cure" means. If you're a patient who has had MS for a very long time, "cure" might mean repair of damage. If you're a parent with MS, you might think of a cure as preventing disease in other loved ones in your family. In many patients, we can completely suppress disease. But, off treatment, could the disease never return? Maybe that's the definition of cure. There are thrilling ideas and, in fact, bedside studies underway to move from suppression of disease to cure. The most likely place that will happen is in people in whom that disease is just beginning.

The second great area of need is more effective therapies for progression. We've thought of MS as having two faces: a relapsing part and a progressive part. Our current treatments are highly effective against relapses but only partially effective against progression. So, the second big goal of current and future MS work is to make a greater impact against progression. That's truly the elephant in the room. Our best current therapies are about 40 percent effective in early progression and about 30 percent effective in later progression. So, for most people with MS today, a cure would mean stopping progression. And we're not there. But there are very hopeful ideas in the laboratory and the clinic.

Infographic References

What are disease-modifying therapies?

- About MS. MS Society. https://www.mssociety.org.uk/

about-ms/treatments-and- therapies (Accessed January 17, 2024) - Disease modifying therapies MS Society. https://www.mssociety.org.uk/

about-ms/treatments-and- therapies/disease-modifying- therapies (Accessed January 17, 2024) - Stem cells. MS Canada. https://mscanada.ca/stem-cells (Accessed January 17, 2024)