Feb 20, 2024, 5:00 am UTC

7 min

Created by

Is Alzheimer’s disease genetic—and should you get tested?

For people who have family members—grandparents, parents, or even siblings—with Alzheimer's disease (AD), the condition may seem inevitable. Yet, experts say, the question, "Will I face the same fate?" can't be easily answered.

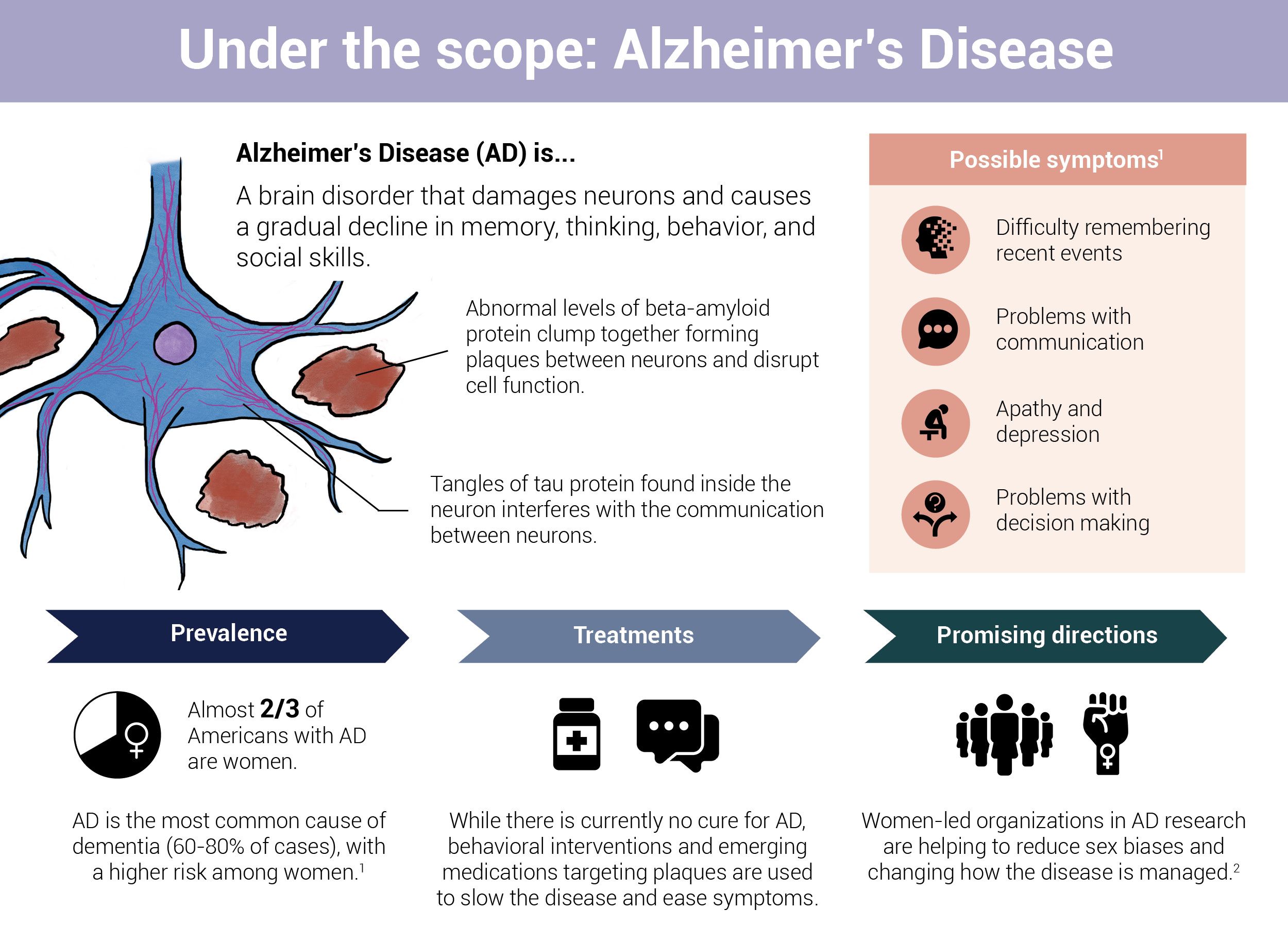

Each of the six million Americans grappling with AD, about two-thirds of whom are women, is on a different journey. Symptoms vary widely, progression is unpredictable, and causes are not well-understood. Amidst this uncertainty, a family history of the condition can seem like the only reliable—and crucial—predictor of one's risk of developing the disease.

It is also easier than ever to look at what you have, or have not, inherited from your parents using new tests that can reveal genetic markers linked with the condition. Some of these tests can even be taken at home. But, as with any breakthrough technology, there is a cautionary tale. Here's the scoop.

This article covers:

Which genes have been identified as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease?

Plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, containing amyloid beta and tau proteins, respectively, are hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease. When these naturally occurring proteins go awry, they begin to clump and tangle inside and around neurons. This disrupts cell function, impairs communication between neurons, and triggers an inflammatory immune response that ultimately degenerates and kills off brain cells.

There are plenty of reasons—some better understood than others—that contribute to the malfunctioning of these proteins. One is problems within the "instruction manual" for protein construction. These instructions are carried by small segments of DNA, also known as genes, that are passed down from one generation to the next. Every gene has two copies or alleles. Together, the pair of alleles—one inherited from each parent—influences everything from eye and skin color to how cells function.

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)

Infographic by Cat Lau. (References below.)However, the process of transmitting these instructions across generations isn't foolproof. Occasionally, an allele can undergo spontaneous chemical changes that alter the genetic code passed down from parent to child.

Researchers have identified more than 60 genes that could be involved in AD. These genes are divided into two broad categories: Deterministic genes and risk genes.

Deterministic genes

Deterministic genes are associated with rare, early-onset forms of AD. Mutations in these genes directly lead to the development of AD with a high degree of certainty.

Fortunately, the likelihood of a person developing Alzheimer's due to the presence of a single deterministic gene is rare. In fact, fewer than 5 percent of all AD cases are considered Familial Alzheimer's Disease (FAD). This type of Alzheimer's is characterized by the inheritance of a mutation in one of the three genes that regulate the production of amyloid beta: Amyloid Precursor Protein (APP), Presenilin 1 (PSEN1), and Presenilin 2 (PSEN2).

- APP (Amyloid Precursor Protein): Think of APP as a bigger protein that gets broken up into smaller fragments known as amyloid beta. When mutations occur in the APP gene, this chopping process goes haywire, leading to the production of too much amyloid beta. These excess amyloid beta fragments clump together in brain cells, disrupting critical cellular processes.

- PSEN1 (Presenilin 1) and PSEN2 (Presenilin 2): Presenilin genes are involved in regulating how—and how much—APP protein gets chopped up in amyloid beta. Mutations in these two genes can change the composition and the levels of amyloid beta in the brain.

Risk genes

Risk (or susceptibility) genes increase one's likelihood of developing AD but do not guarantee the condition. These genes are linked with a common type of AD, known as Late-onset Alzheimer's Disease or LOAD, which typically begins around the age of 65 and is influenced by a variety of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. LOAD is sporadic, meaning it does not run in families.

Below are a handful of risk genes associated with AD, but dozens of others have been discovered:

- APOE (Apolipoprotein E): The APOE gene has three common forms or alleles called e2, e3, and e4. Studies show that the APOE e4 allele is associated with increased amyloid beta buildup in the brain. The exact reasons behind this accumulation remain unclear, but researchers hypothesize that it is connected to APOE e4's role in the metabolism of lipids (fats) and cholesterol in the body.

- People who inherit one copy of the APOE e4 have an increased lifetime risk of developing Alzheimer's. Those with two copies of this allele have an even higher lifetime risk of developing the disease. (This association is particularly true for people of non-Hispanic White descent.) Additionally, women with an APOE e4 allele are at a significantly higher risk of developing AD than men.

- CLU (Clusterin): The CLU gene helps produce a protein called clusterin, which is crucial for degrading and clearing up amyloid beta in the brain. However, certain variations of this gene result in the production of a less efficient type of clusterin. This inefficiency can lead to a buildup of amyloid beta.

- SORL1 (Sortilin-related receptor 1): SORL1 acts like a traffic controller in the brain, determining what happens to the protein APP. Normally, SORL1 steers APP away from a pathway that produces amyloid beta. However, certain variations of SORL1 don't do this job as effectively, leading to an overproduction of amyloid beta.

It is important to note that much of what is known about the genetic risk of Alzheimer’s is based on research with White participants of European ancestry. It is much less clear how genetics influence susceptibility to AD in other populations.

APO e4 allele

- An estimated 20 to 30 percent of individuals in the United States have one or two copies of APOE e4.

- Approximately 2 percent of the U.S. population has two copies of APOE e4.

Source: Alzheimer's Association

Does a person’s sex influence a person’s genetic risk of Alzheimer’s?

The short answer is yes. Furthermore, there is emerging evidence that sex differences in genetic risk go beyond APOE e4, which increases the likelihood that a female with either one or two copies of the allele will develop Alzheimer’s. Researchers at the University of California, San Diego, developed Alzheimer’s risk scores for males and females by combining the effects of dozens of genetic changes, most associated by themselves with only a small risk of the disease. They found that the risk scores were better at predicting age at onset and disease-related brain changes when matched to sex, i.e., male risk scores matched to males; and female risk scores matched to females. The results suggest a person’s sex influences their genetic risk of Alzheimer’s, though which genetic changes are responsible is still unclear.

Should you get a genetic test for Alzheimer's—weighing its merits and drawbacks?

Genetic testing for Alzheimer's isn't routine, though it is increasingly common. In fact, there are no reliable tests that can predict the most common form of Alzheimer's: Late-onset AD. However, tests for the rare genes that directly cause Alzheimer's and APOE e4 are available, and a doctor may recommend them under specific circumstances.

Ekaterina Rogaeva at the Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Diseases at the University of Toronto has spent the last 30 years conducting genetic research in Alzheimer's and contributing to the development of tests that can look for markers associated with the condition. However, until recently, these tests haven't been doctors' go-to to determine Alzheimer's risk.

For one, there haven't been any effective treatments on the market that can slow the progression of the disease. "In that case, the knowledge can only cause intense stress and make people nervously hope that they escape this devastating condition," says Rogaeva.

And, not to forget, genetic mutations aren't the only culprits in this disease—environmental and psychosocial factors like diet, exercise, social engagement, and even education strongly influence cognitive reserve, the brain's ability to cope with changes that would otherwise lead to AD.

Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease include:

Family history: Having a close family member (a parent, brother, or sister) with Alzheimer's disease increases an individual's risk of developing it.

Genetics: Various genetic mutations can increase the risk of Alzheimer's, though only a few gene changes directly cause the disease.

Age: The greatest risk factor for Alzheimer's disease is age.

Traumatic brain injury: People with previous brain injuries may be at higher risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

Heart health: Damage to the heart or blood vessels caused by heart disease, diabetes, stroke, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol may increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

Lifestyle: Modifiable factors such as diet, sleep, exercise, smoking, alcohol consumption, and social connection can influence Alzheimer's risk.

But things have shifted with the approval of Leqembi. This drug can remove the buildup of amyloid beta and slow down the rate of cognitive decline in people with Alzheimer's but with the risk of swelling and bleeding in the brain. Now, genetic tests for the disease are on the rise: An analysis shows, in the months leading up to Leqembi's approval in the U.S., the number of people over 55 undergoing APOE e4 genetic testing increased by 125 percent.

In some situations, tests may help guide treatment decisions. For example, individuals with the APOE e4 allele have an increased risk of severe side effects from anti-amyloid drugs. The caveat is that a high genetic risk score doesn't always guarantee that a person will develop the disease. In fact, findings of a 2019 study published in the journal JAMA suggest that a healthy lifestyle can help offset the genetic risk of dementia. A group of researchers in the United Kingdom followed 200,000 people with varying levels of genetic risk for dementia over eight years, assessing their lifestyle habits. They found that among people with a high genetic risk, only 1 percent of those who maintained healthy lifestyles developed dementia. In contrast, nearly twice as many individuals with poor lifestyle habits went on to develop dementia.

"One limitation, though, might be how we think about genetic risk—most research is conducted in Caucasian males, so we don't understand sex and race-based genetic differences in Alzheimer's as well as we should," Rogaeva says.

The Alzheimer's Association in the United States and the Alzheimer's Society of Canada caution against genetic testing for Alzheimer's in healthy individuals. At-home genetic tests, which don't require physician approval, are a particular concern because counselling may not be available to help people interpret the test results.

Ultimately, genetic testing, as it stands today, isn't a fit, or even effective, for everyone. Relying on it to diagnose Alzheimer's is like assembling a jigsaw puzzle with only a fraction of the pieces—helpful but far from complete.

Infographic references

- 2023 Alzheimer's Facts and Figures: Special Report, Alzheimer's Association (Accessed June 20, 2023)

- Castro-Aldrete L, Moser MV, Putignano G, Ferretti MT, Schumacher Dimech A and Santuccione Chadha A (2023) Sex and gender considerations in Alzheimer’s disease: The Women’s Brain Project contribution. Front. Aging Neurosci. 15:1105620.